#12 Golden Age of Hollywood Series

The quote above is from a review published in Vanity Fair magazine. It is just another example of how the censors in the 1930s were wringing their hands over the movies instead of worrying about more important things.

It looks so silly to us now, in the modern era, when we’ve moved past the belief that a movie could inspire violence.

Those people in the 1930s and their quaint movie violence and their old-fashioned, paternalistic worries about the impact of art on society.

It’s a nice thing to tell ourselves. There’s only one problem.

This review wasn’t written in 1932 about Scarface.

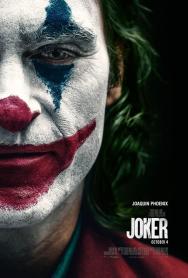

It was written last year about Joker, a film starring Joaquin Phoenix is his Oscar winning role as psychopathic Arthur Fleck who rises to glory among disaffected American men when he murders someone on live television.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

After the trouble with the censors on Hell’s Angels, Howard Hughes doubled-down.

It was almost as if he went looking for the most objectionable film he could possibly make as a follow up.

It was almost as if he took the ban on gangster films as a dare.

He made Scarface, at least in part, for the shock value. Just like Joker.

In the film Scarface, screenwriter Ben Hecht wrote a script based loosely on Al Capone, who had a scar on his face like the one Tony Camonte sports in the film. He also drew inspiration from the Borgias, a treacherous Spanish family that ascended to power and the papacy in the fifteenth century and was accused of murder, adultery, and incest.

The Hays Office warned Hughes not to make the film, and vowed that people would not see it if he did.

Hughes sent his director Howard Hawks a memo: “Screw the Hays Office. Start the picture and make it as realistic, as exciting, as grisly as possible.”

Hawks did. The film follows a similar line as the Warners Brothers gangster films, but with more graphic violence. Tony Camonte bullies his way up the ladder of organized crime, using a machine gun to mow down anyone who gets in his way. He builds a fortress with steel doors and windows to protect himself from his enemies, and explodes in jealous rages when his sister so much as looks at another man.

Scarface gloried in its excesses—Tony murders, steals, and lies with reckless abandon.

The Hays Office had never outright rejected a film, but it came close with Scarface.

It demanded changes—primarily around removing the insinuations of incest between Tony and his sister. (In the original version, Tony tears her dress and slaps her after seeing her dancing with a man. When he discovers she’s eloped, he murders her new husband in cold blood, even though he’s a trusted friend and business partner.)

They also wanted changes in the ending—in a lost version, after the cops surround him, Tony runs into the street firing his machine gun. They don’t take him down until he’s emptied of bullets, and the movie ends with the clicking sound of him firing empty rounds as he dies.

But for once the Hays Office had success in suppressing a movie, and very few people saw the uncut version. The film was banned outright in multiple states and after its initial run, it was unseen until 1980, when Universal bought the rights and released it on video.

Howard Hughes was incensed that the censors had ruined his film, and believed their effort was politically motivated. He left Hollywood after Scarface, and did not make another film for ten years.

Since he died in 1976, it is impossible to know what Hughes would have thought of the gory remake of his film in 1983. Likely he would have been envious, for Al Pacino’s Scarface gloried in violence, foul language, drugs, and sex.

Fifty years after the fact, director Brian De Palma got to make the unrepentantly shocking film Hughes wanted.

As to whether or not Hughes would’ve liked Joker, I couldn’t hazard a guess.

Want more? Click here for an index of all posts in this series, as well as source notes and suggested reading.